Warning: this is going to require a good bit of physics and math.

If that’s not your thing, fair enough, feel free to bail.

But I’m going to try to make this as palatable as I can.

So give it a go, if you’re feeling up to it.

Let’s start with the math of how crystallography really works.

X-rays (wavelength λ=10⁻¹¹-10⁻⁸ m; energy 0.02-20 keV) scatter, elastically, off of electrons bound to atoms, producing spherical waves of the same wavelength.

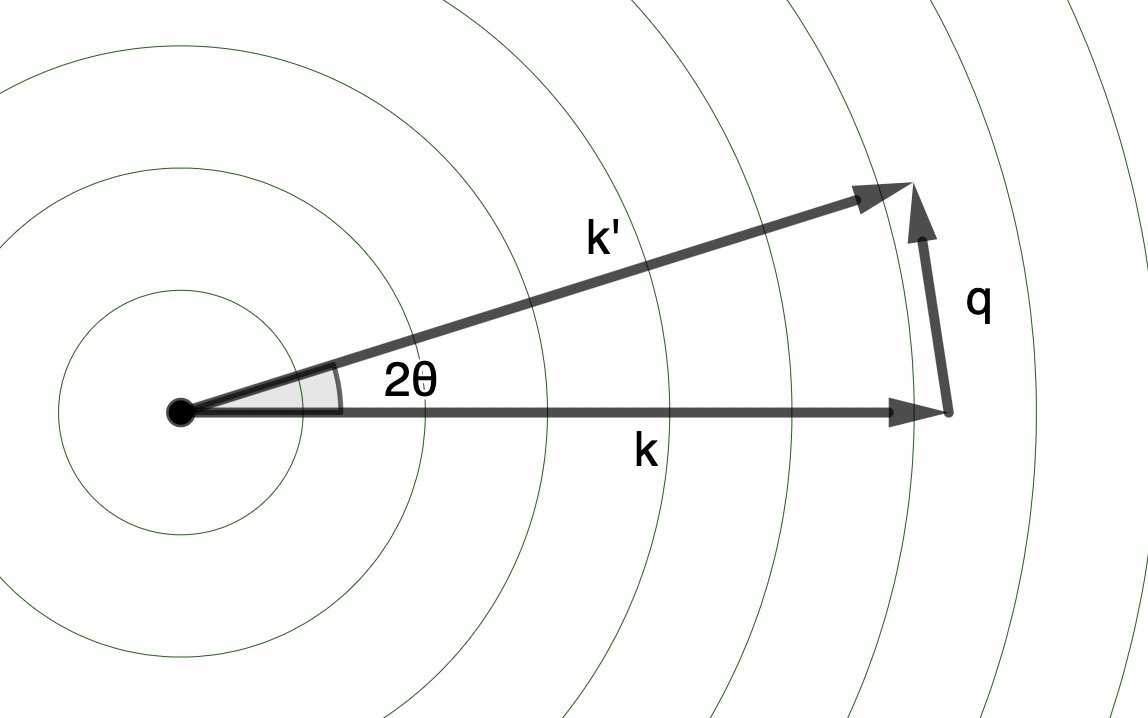

We can describe the direction of traveling wave using a “wavevector” \(\mathbf{k}\), with the magnitude of the vector equal to the “wavenumber”, \(\frac{2\pi}{\lambda}\), and the direction pointing in the direction of propagation. For the incident X-ray plane wave, there is a single, definite wavevector (\(\mathbf{k}\)). For the scattered wave, there are many, equivalent wavevectors (\(\mathbf{k}'\)), one for each scattering angle.

The difference in direction between the incident (\(\mathbf{k}\)) and scattered (\(\mathbf{k'}\)) wavevectors is given by the “scattering vector”, \(\mathbf{q} = \mathbf{k'} - \mathbf{k}\).

Its magnitude is given by \(\lvert \mathbf{q} \rvert = \frac{4 \pi \sin( \theta )}{ \lambda }\), where \(2 \theta\) is the scattering angle.

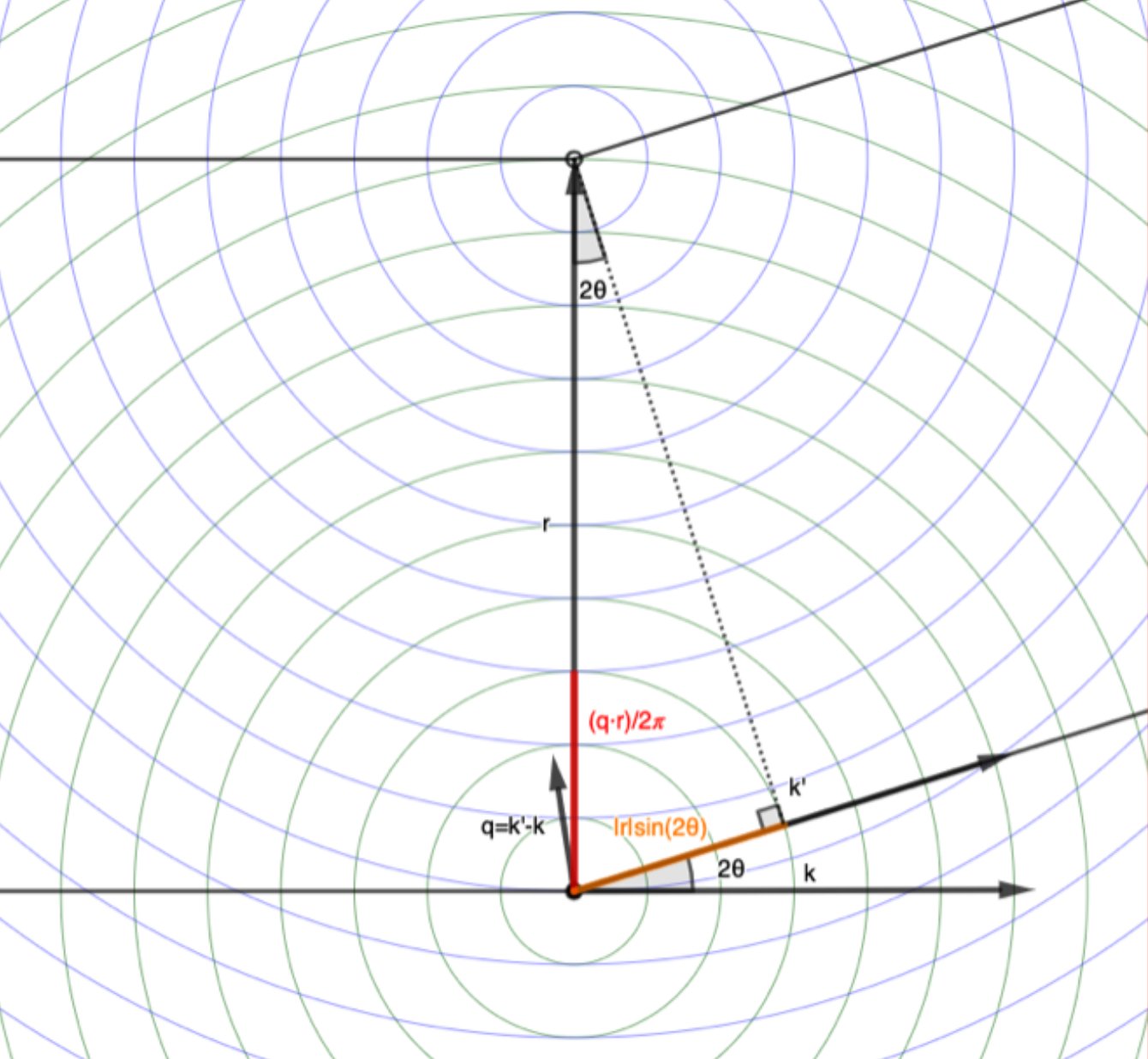

If there are multiple electrons scattering the incident wave, separated by a vector \(\mathbf{r}\), the scattered waves will differ by a phase shift given by the dot product of \(\mathbf{q}\) and \(\mathbf{r}\): \(\Delta \phi = \mathbf{q} \cdot \mathbf{r}\).

Why?

This is just the difference in path length, \(l\), converted to radians:

\[\Delta \phi = \mathbf{q} \cdot \mathbf{r} = |\mathbf{q}||\mathbf{r}|\cos(\theta) = \frac{4 \pi \sin(\theta)}{\lambda} |\mathbf{r}| \cos(\theta) = \frac{2 \pi}{\lambda} |\mathbf{r}| 2\sin(\theta)\cos(\theta) = \frac{2 \pi}{\lambda} |\mathbf{r}| sin(2\theta) = \frac{2 \pi}{\lambda} l\]

The effect of this phase shift can be expressed by way of a complex exponential, called the “phase factor”:

\[e^{i \Delta \phi} = e^{i \mathbf{q} \cdot \mathbf{r}}\]

This phase difference then corresponds to turning a unit vector in the complex plane by the angle \(\Delta\phi\).

If \(\Delta\phi = \mathbf{q}\cdot\mathbf{r}\) is such that the path length difference (\(l\)) is some multiple of the wavelength (\(\lambda\)), in the far-field diffraction limit the waves will constructively interfere, giving a phase factor of 1:

\[l = n \lambda \rightarrow e^{i \mathbf{q} \cdot \mathbf{r} } = e^{i 2 \pi n} = 1\]

So, given a set of atoms at positions \(\mathbf{r}_{i}\) we can compute the effect of the interference in far field, at any scattering angle, by computing the phase factor \(e^{i \mathbf{q} \cdot \mathbf{r}_{i} }\).

(The problem, as we will see, is that crystallographic experiments starts from the exact opposite state of affairs: we measure the diffraction pattern that results from the scattering of X-rays, and we don’t know the positions of the atoms responsible for the scattering.)

Now, electrons bound to atoms scatter differently from isolated electrons, depending on the atom’s distribution of electron density.

This difference is represented with the “atomic scattering factor” \(f_{n}(\mathbf{q})\) for each atom (indexed by \(n\)).

We can calculate this atomic scattering factor by integrating over the whole atom’s electron density, weighting the density at each position around the atom (\(\rho_{n}(\mathbf{r})\)) by the scattering factor:

\[f_{n}(\mathbf{q}) = \int \rho_{n}(\mathbf{r}) e^{i \mathbf{q} \cdot \mathbf{r}} \mathrm{d}^{3} \mathbf{r}\]

In a system of many atoms (say, a molecule) at positions \(\mathbf{r}_{n}\), the scattered wave has an amplitude equal to the sum of the contributions from each atom.

This is called the “Molecular Form Factor” (\(F(\mathbf{q})\)):

\[F(\mathbf{q}) = \sum_{n} f_{n}(\mathbf{q}) e^{i\mathbf{q}\cdot\mathbf{r}_{n}}\]

Rather than working with atoms as though they are discrete pockets of electron density, we can instead extend the molecular form factor to a continuous distribution of electron density for the whole system (\(\rho(\mathbf{r})\)) by switching from a discrete sum to an integral over the entire scattering volume:

\[F(\mathbf{q}) = \int \rho(\mathbf{r}) e^{i\mathbf{q}\cdot\mathbf{r}} \mathrm{d}^{3}\mathbf{r}\]

Look familiar?

This, my friends, is magic.

Elastic scattering converts plane waves to spherical waves. The interference of these scattered waves performs a mathematical operation.

How cool is that?

In the next part, we’ll talk about how we actually measure these scattered waves.

Then, we’ll move on to talking about how things change when we measure the scattering from a molecular crystal rather than just an arbitrary distribution of electrons.

Until then, be well :)

Part 2 here